We are constantly bombarded by (elite-money-backed) economic messaging pimping demands for “more innovation,” “more growth,” and “more productivity” in neatly-packaged pleas for more immigration (e.g. Marketwatch, Cato, Brookings, CFR, Forbes). In fact, there seems to be an ongoing campaign of “more immigration!” op-eds.

So what’s Congress doing during their “lame duck” session while the rest of us are putting up our trees, making our travel plans, and looking forward to family gatherings?

Congress is again entertaining “Dreamer” and farmworker amnesties and the EAGLE Act – not border enforcement, not pausing guest worker programs in spite of huge waves of layoffs.

But last Friday, The New York Times again stumbled across a troubling and harmful long term trend:

Men have been withdrawing from the labor force for decades. In the years following World War II, more than 97 percent of men in their prime working years — defined by economists as ages 25 to 54 — were working or actively looking for work, according to federal data. But starting in the 1960s, that share began to fall, mirroring the decline in domestic manufacturing jobs.

Read the whole story if you have time – there’s a lot more quality information in the coverage than just the quote above. It’s quietly satisfying to get to the end, consider the question “so in light of this, should we have more or less immigration?” and know there is only one reasonable answer.

Similarly, we’ve long been promised that our high immigration levels create a boon of productivity, but with ample evidence that the outcome isn’t what was sold, we need to urge Congress to demand a different strategy.

Quietly Quitting Productivity Gains?

In a Bloomberg column by Conor Sen I came across the other day, he noted:

“Yes, productivity growth was lower in the 2010s than it had been in decades. But the Fed’s mandate isn’t just to boost profitable or productive economic activity. It’s also aiming for full employment and 2% inflation. And to the extent the tens of thousands of tech job cuts recently announced are due to a normalization of interest rates, it stands to reason that the Fed’s policy actions in the 2010s helped support those jobs at a time when the labor market still needed support.”

Excuse me? Why did the tech jobs labor market still need structural support? We’ve been told that “high skilled” immigration and worker programs like H-1Bs create jobs, not take them (we know better, of course, but the dominant narrative has long been set). Sen points out that, in hindsight, Apple’s restrained approach in the 2010’s of “using its cash to do stock buybacks and dividends rather than investing in self-driving vehicles and other technological moonshots” looks like the right one”.

We have too much immigration and there’s something broken and unhealthy about our productivity outcomes.

The George W. Bush Center asks:

“If immigration makes the economy larger, more efficient and productive, what’s the problem? Why do we, as a nation, strictly limit immigration?”

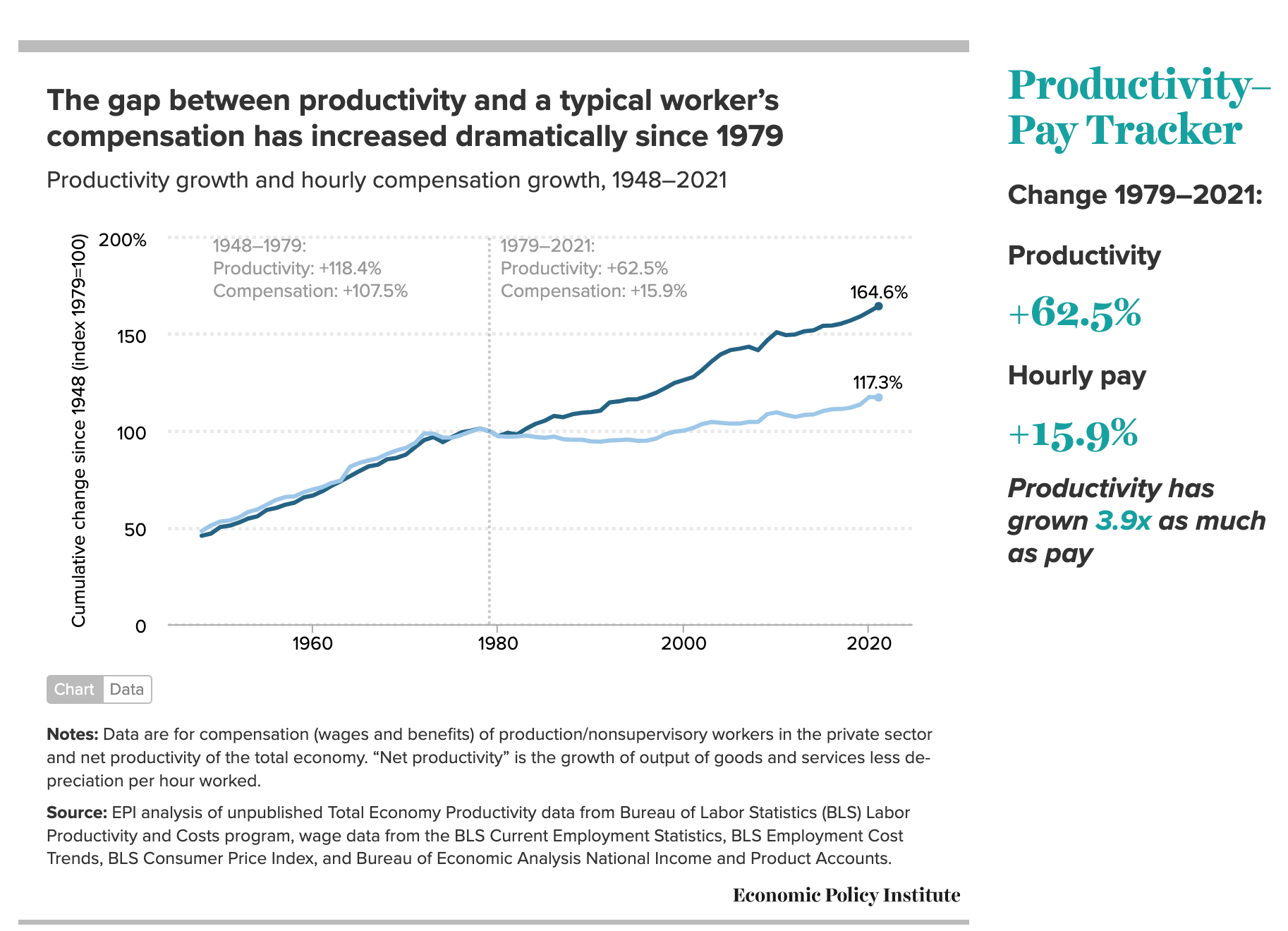

While immigration does make the economy larger (as you would expect), the evidence that it is making the economy more efficient and productive seems mixed at best. On the one hand, we’ve seen productivity continue to grow (in some measurements) while breaking their tie to wage growth during this Second Great Wave of Immigration:

When you pair that graph with housing’s increasing unaffordability, you’ve got the slow-motion decline of the American Dream.

But to dig deeper on the topic, let’s look at this report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which indicates that there are serious questions and unknown or unexplained factors as to why productivity levels (by other measurements) have departed from earlier historical trends (during low immigration periods):

While the conversation currency of our era is brash certainty, it’s worth taking a few moments to consider the types of uncertainties that should lead us to use our common sense and knowledge of history to determine the course of action. Think of concepts like “Multifactor Productivity Growth” whenever you are next confronted with open border economist talking points.

They don’t know. But we all have a sense that the way things are going is not working and not giving reason for optimism about the future and how our kids and grandkids will do down the road. You see that in polling consistently.

We need a Great Tightening of our borders and our labor force. We need to stop the failed approach of mass immigration, restarted in 1965 and pumped up on steroids in 1990. We need to assimilate the wave of foreign born Americans. We need to be confident in our ability to succeed in a modern, low-population growth economy. And we need to trust how our people might respond with fluctuating birth rates if a new aggregate optimism is born.

There’s one other thing to remember about the low-productivity 2010s. Imagine how much worse it could have been had the many Congress and their supporters in business and media gotten the massive increase in immigration that they were oh-so-close to delivering with the Gang of Eight bill. And take note that none of the economic pundits ever look back at trends they can finally admit are unfavorable and blame a lack of higher immigration.

There remains plenty of worthwhile economic data that points to how much of a failure high immigration continues to be… you just have to dig a bit further and take note of what isn’t being said.

ANDREW GOOD is the Director of the Media Standards Program for NumbersUSA

Take Action

Your voice counts! Let your Member of Congress know where you stand on immigration issues through the Action Board. Not a NumbersUSA member? Sign up here to get started.

Donate Today!

NumbersUSA is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that relies on your donations to works toward sensible immigration policies. NumbersUSA Education & Research Foundation is recognized by America's Best Charities as one of the top 3% of well-run charities.

Immigration Grade Cards

NumbersUSA provides the only comprehensive immigration grade cards. See how your member of Congress’ rates and find grades going back to the 104th Congress (1995-97).